Field service software implementation usually starts long before anyone logs into the system. It begins the moment schedules, job details, and status updates stop living in calls, chats, and notebooks and move into one shared workspace. At this stage, the software itself is rarely the problem. The real challenge appears when technicians are expected to rely on it during a busy workday, between sites, delays, and last-minute changes. That is why implementation is less about configuration and more about whether the system fits how field work actually happens – under time pressure, on the move, and without room for extra steps.

Field service software implementation is not a single setup step or a technical installation. In practice, it is a controlled process where a system is introduced into live operations while existing workflows continue to run. Implementation goes beyond setting up features in the system. The software has to fit how dispatchers actually assign work, how jobs move during the day, and how reports are filled out in the field. Office staff, technicians, and managers usually start using the system at different moments, depending on what they need from it.

What matters most is how the software fits daily work under time pressure. When implementation reflects real field conditions, adoption starts earlier and friction stays lower.

In field service, new software usually works as designed. The problem starts later, in everyday use.

Technicians work between sites, answer calls, rush to the next job, and often deal with unstable connections. If a system feels slow, adds extra taps, or interrupts familiar routines, it gets ignored. Jobs are closed later, details are skipped, and the data stops matching what actually happens in the field.

This is not about attitude or resistance to change. Adoption breaks down when implementation does not match real working conditions. When mobility, speed, and simplicity are underestimated, technicians adjust by working around the system instead of inside it.

Adoption often fails before technicians even touch the system. It breaks at the planning stage, when real field work isn’t reflected in how the software is rolled out.

When implementation is rushed, technicians notice friction immediately. Job statuses don’t match real actions, updates add steps instead of removing them, and the system feels like extra work. Usage becomes minimal and forced.

In smoother implementations, workflows are aligned upfront. Job states reflect what actually happens on site. Updates replace phone calls. The system starts helping technicians stay oriented instead of slowing them down.

How the rollout is positioned also matters. If software is introduced as a control tool, adoption drops. If it’s framed as a way to reduce confusion, usage grows naturally. Implementation strategy doesn’t teach adoption. It sets the conditions for it.

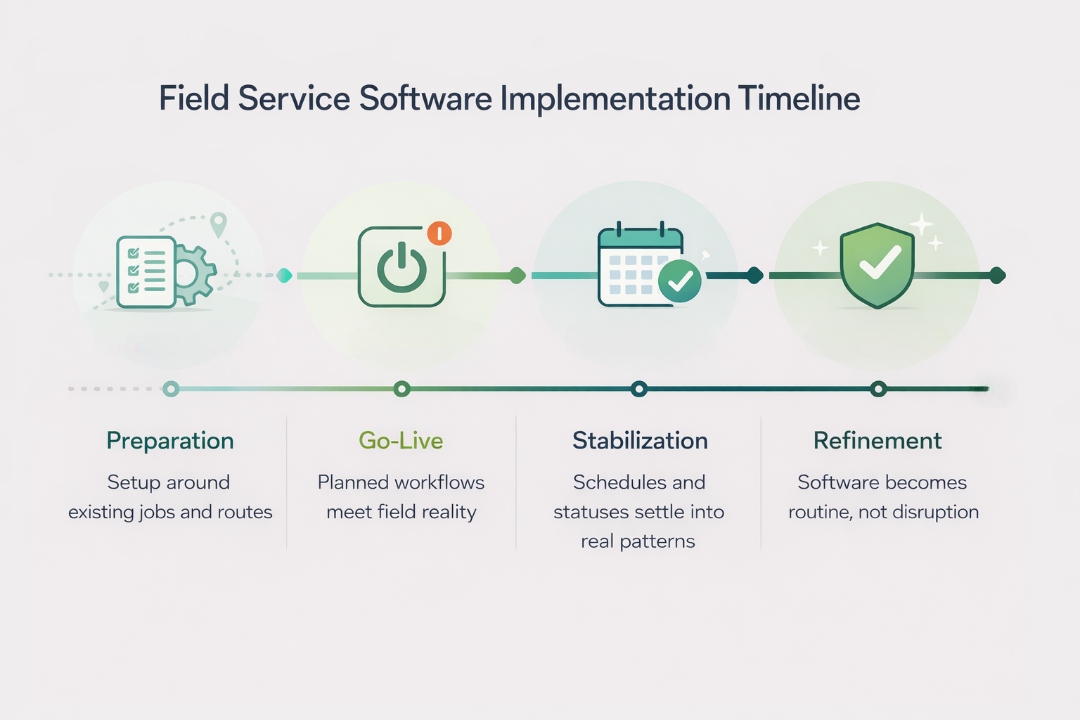

Implementation in field service almost never feels like a single launch. It stretches over time and changes shape as the system meets real work.

At first, teams prepare the ground. The software is configured around existing jobs, routes, and roles, but technicians are not fully dependent on it yet.

Then the system goes live. Some tasks move into the new interface, others stay outside. This is usually when mismatches between planned workflows and field reality become obvious.

Over time, usage settles. Schedules, statuses, and reports start reflecting how work actually happens, not how it was expected to happen. Only later does refinement begin. Small adjustments replace workarounds, trust grows, and the software becomes routine rather than an event.

Field service software implementation succeeds or fails long before technicians form an opinion about the tool. Adoption follows the quality of the rollout: how well the system reflects real workflows, how predictable it behaves in daily use, and how clearly it supports work in the field.

When implementation aligns system logic, operational processes, and human behavior, adoption grows naturally. The software stops feeling imposed and starts functioning as shared infrastructure.

If you’re evaluating field service software implementation for your team, focus on how the system fits real work patterns and how adoption develops over time. This perspective makes long-term use far more likely than any single launch decision.

Why do technicians often resist new field service software at first? For technicians, new software often shows up in the middle of a busy workday. They are asked to tap screens, change habits, and think about reporting while standing on site or moving between jobs. Until the system proves useful in real conditions, it is treated as extra effort rather than help.

How long does field service software implementation usually take? There is no single finish point. Access can be granted in days, but real adoption appears only after the system survives busy schedules, delays, and last-minute changes. For most teams, this takes several weeks of everyday use.

Can field service software be implemented without disrupting daily operations? In practice, daily operations continue while the system is being introduced. Teams often run old and new workflows in parallel for a short period, which keeps jobs moving. Disruption is usually minimal when implementation focuses on alignment with existing work patterns rather than forcing abrupt changes.

Is technician training enough to ensure software adoption? Training helps users understand the interface, but it does not guarantee daily use. Technicians adopt tools that save time on actual jobs and reduce back-and-forth with the office. If the system slows work in the field, training alone does not compensate.

What typically causes software implementation to fail in field service teams? Failures usually occur when software conflicts with real field workflows. Systems that add steps, fragment job information, or behave inconsistently under pressure lose trust quickly. Once confidence drops, usage fades regardless of features.